Latin America This Week: September 14, 2023

AMLO ups spending, favoring the middle class and the military; Uruguay’s financial stability attracts investment—and crime follows; Peru’s democratic backsliding is passing the point of no return.

September 14, 2023 12:32 pm (EST)

- Post

- Blog posts represent the views of CFR fellows and staff and not those of CFR, which takes no institutional positions.

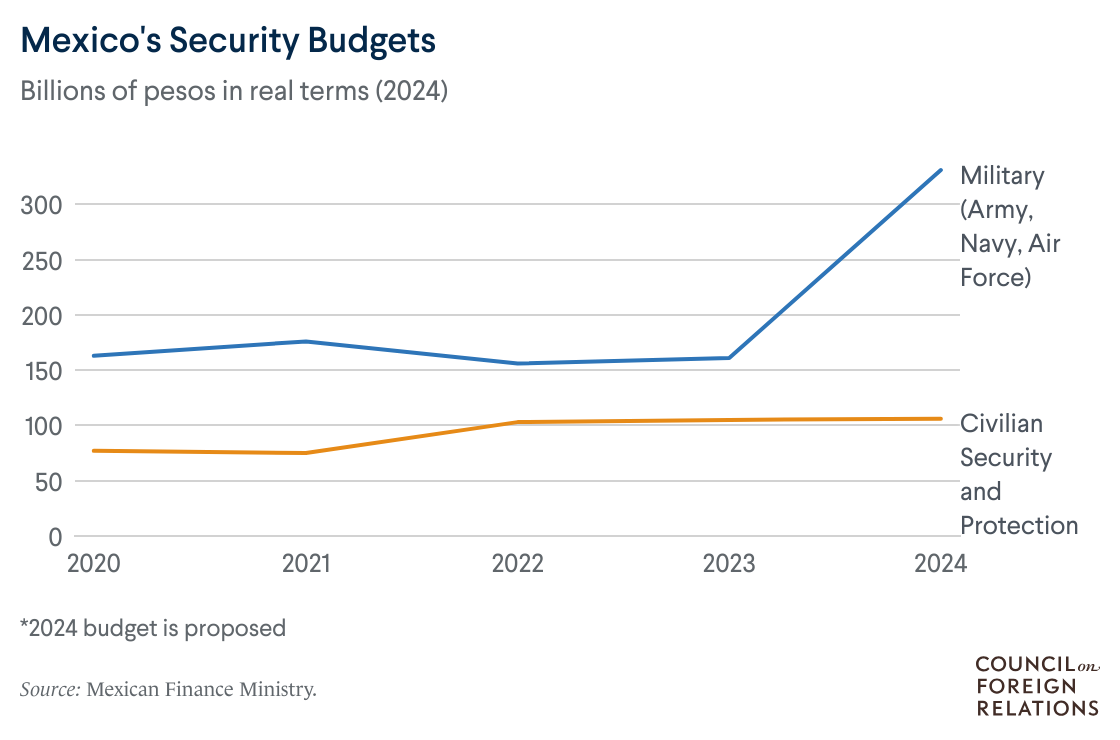

AMLO ups spending, favoring the middle class and the military. Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s (AMLO’s) proposed budget for 2024 came in at just over 9 trillion pesos, roughly US$512 billion, 4.2 percent more than 2023. Universal pensions topped the list at nearly 1.5 trillion pesos, up almost 10 percent in real terms since 2019. This has tilted social spending away from the poorest toward the middle class, and from the young to the elderly. Healthcare too took a hit with the ministry’s budget slashed by half, despite the tens of millions of Mexicans that remain without access.

The military’s proposed budget more than doubled, as the army now manages Mexico City’s new airport, the revived Mexicana airline, and the construction of a 1,000-mile train on the Yucatán Peninsula. The Navy’s budget too has grown to cover the costs of managing ports, airports, customs, and building a railway connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Civilian police force spending, despite elevated rates of violence and homicides, flatlined.

The bump in spending means more debt. Despite talk of austerity, Mexico’s sovereign debt will grow by nearly 60 percent over AMLO’s tenure, rising from 43.6 percent of GDP in 2018 to roughly 49 percent in 2024. Add in Pemex’s pseudo-sovereign obligations—now over US$110 billion—and the government’s debt comprises roughly 53 percent of GDP. And the gap between revenues and outlays is growing, this year by over 40 percent.

If this budget passes in its current form, AMLO leaves that new leader with more fiscal and financial constraints than he faced.

Uruguay’s financial stability attracts investment—and crime follows. Repeated economic and political crises in neighboring Argentina and Brazil have made Uruguay something of a financial hub despite its smaller economy. The country attracted nearly US$10 billion in foreign direct investment in 2022, triple 2021 levels, and accounting for over 13 percent of the country’s GDP. The country’s reputation for financial stability hasn’t gone unnoticed by those with ill-gotten gains. A recent government report shows money laundering cases tied to drug trafficking nearly doubled between 2018 and 2022. The increase in crime is, in part, a consequence of Uruguay’s limited enforcement resources and personnel according to InSight Crime. Indeed, despite opening thousands of money laundering investigations each year, the government only charges a handful of suspects and convicts even fewer. And 2020 legal changes that raised the legal limit for cash payments from US$4,000 to US$100,000 make it easier to hide the provenance of funds.

Peru’s democratic backsliding is passing the point of no return. When demagogues-in-chief like Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez or Nicaragua’s Daniel Ortega lay siege to democratic institutions, it makes the news. Peru’s democratic backsliding is advancing just as quickly as Venezuela’s or Nicaragua’s once did, but it’s attracting just a fraction of the international attention—most likely, because it’s taken a less familiar form, with a congress taking the lead, and because its protagonists do not share any one ideology or party. Since Dina Boluarte took over the presidency from Pedro Castillo earlier this year, a loose “pact” of factions in control of Peru’s extremely unpopular congress has packed a growing number of democratic institutions with pliant cronies and staved off demands for early elections. On September 8, the pact escalated its attacks on democracy, voting to investigate Peru’s National Justice Board (JNJ), which names judges and prosecutors. The investigations are likely to culminate in greenlighting a purge of the JNJ, opening the door to a wholesale takeover of top posts within the judiciary. The timing isn’t accidental: within six months, Peru is scheduled to appoint new heads to its elections body, a process in which the JNJ has a major role. With the JNJ under its control, the factions that control congress could tamper with 2026 elections, jeopardizing free and fair elections for years to come. Although the United Nations’ office in Peru denounced the Peruvian congress’ latest maneuver, Brussels and Washington have kept mostly quiet since insisting on accountability for the killing of dozens of protestors by security forces earlier this year. Washington has leverage over Boluarte, but little ability to sway members of Congress or their backers. Still, a democratic breakdown in Latin America’s fifth-most-populous country and sixth-biggest economy is no small matter, and will have destabilizing consequences for the region if no one hits the brakes in time.

Online Store

Online Store